The ever-erudite Rob Reid dropped me an email a little while ago asking some questions for a paper he's writing on games and performance. Rob is one of the architects of Pop-Up Playground, the Melbourne gathering that has brought together a whole fascinating world of participatory makers, from digital gaming to interactive theatre to roleplaying to escape rooms, and on.

It felt like a good opportunity to wrap some thinking around Boho's practice, where it's come from, how we think about our work, what we're aiming for next. So, here goes.

How do you approach the design process for your interactive work?

Boho’s process really centres around working with research scientists - typically climate or systems scientists, but also urban designers, epidemiologists… Our shows usually draw on concepts from sustainability science, systems thinking, game theory, network theory, complex systems science, resilience - these fields which are often gathered together under a broad heading of ‘complexity’.

Basically, we’re looking at any sort of system in which lots of different elements are interconnected, and what arises from those interconnections. That’s the raw material for our games.

Working with scientists, we’ll go back and forth with them, building up our understanding of the system - whatever that system is - and creating a systems model. That model - which usually looks like a flowchart diagram, plus a whole series of maps, lists, other visualisations - becomes the basis for the show we build.

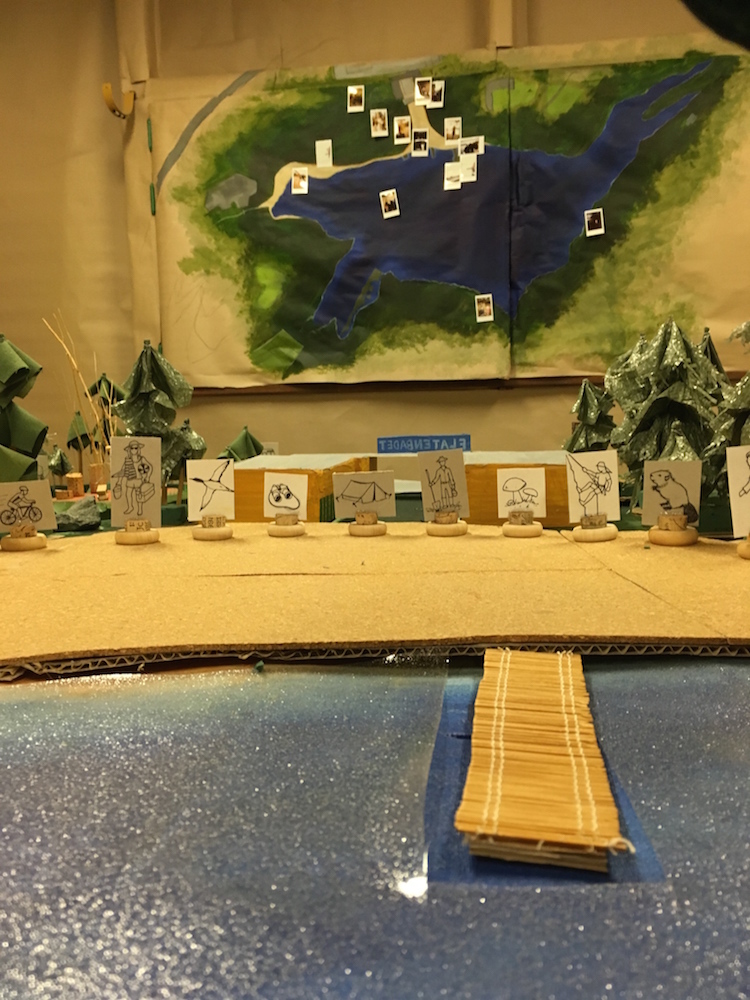

An example of the kinds of systems models we construct / adapt in our work.

An example of the kinds of systems models we construct / adapt in our work.

We then go through that systems model, looking for key linkages and systems dynamics we can turn into games.

In the last couple of years, we’ve started breaking things down into two kinds of interactive activities - what we’ve dubbed ‘skilltesters’ and ‘games’.

‘Games’, in this parlance, involve choice - any kind of decision-making, resource allocation, negotiation, etc. Anything where the audience needs to predict how the system will behave, and make a call about what they’d like to see happen. Things where they have to use their strategic brain.

The other kind are ‘skilltesters’ - games where the purpose is just to win. Can you fly this bird over here holding it between two sticks, can you sort these counters out into piles of different colours in less than 30 seconds, etc… These games are often more active, more playful, and we use them to give us inputs into our system model, so we can read out different scenarios. But we don’t hinge big choices on them.

Most shows will have a mix of these kinds of activities - some games where the audience is making key decisions, thinking through problems and coming up with strategic solutions, and some skilltesters where we’re introducing ideas more playfully, giving them a quick input into the show without too much weight being placed upon their choices.

How do you account for the unexpected in your work?

Look, we’re not improvisers - we build a structure with some different pathways, some resilience to shock etc, and then we guide audiences through it. There’s room for discussion, but in some senses there’s still the chance that the audience can break the show.

That said, one major advantage we have in building an experience is that we’re very transparent with our aims - ‘we’re here to talk about this concept, we’ve made these games that do that, here’s how it’s gonna work’. The performers are usually playing themselves, facilitating and helping the audience. So, for example, when Nathan was running a piece of ours called Volleyball Farm for a Forum for the Future event in London in Nov, the game broke because we’d never calibrated it for more than 5 players. But Nathan was able to discuss the intention behind playing the game, what point we wanted to illustrate, and that worked almost as well.

Can you describe the encounter between a participating audience and your work? (ie, what's it like to play?)

We go for gentle, non-confrontational, casual. Me, I get more anxious and stressed as a participant in interactive shows than anyone, and we make putting the audience at ease the key watchword.

So you’ll be met - in say a foyer, if we’re doing it in a theatre - and you’ll be told what’s going to happen, and you’ll be guided to a table, or to your seat - given a little more of a heads up about what’s going to happen - and then you’ll be introduced to the facilitators, and then you get your hands on whatever it is. Gentle, all the time.

The games themselves, often are drawn from boardgaming, and there’s a well established practice in boardgaming of how to introduce rulesets to players - good, thoughtful advice I think we’d do well to learn from. There’s an order to how you introduce information:

1. Who you are in the game2. What your objective is3. How you achieve that objective4. What does a turn consist of

and so on. Not always appropriate, but it’s nice to have a clear, logical structure for how information goes.

The experience is often divided roughly into three different forms: games/interactive components, theatre/narrative, and performance lecture. We’d tend to cycle between these three forms rapidly over the course of a show, with the weight shifting between them as we build to the end.

How does narrative/mood/meaning emerge from the experience of your work?

It all happens in the post-show discussions!

Well, mostly. We usually build a show with a post-show chat built in - a conversation with a guest scientist or an expert in the field we’re discussing. Then we’ll have a glass of wine, and a really informal conversation with the audience. That’s where the ideas underlying the show get unpacked, that’s our chance to dive in deeper.

Of course, that’s not to say that the show itself doesn’t also bring out the ideas, but we think that explicit conversation afterwards is really important.

What/who have been your influences?

We started off making interactive work in Canberra with no-one else around doing it - not in the way we were, anyway. We knew we weren’t the only ones making it, but we couldn’t easily find out who else was out there, and what their stuff looked like. So we made a lot of stuff up.

Our initial impetus was to do computer games live on stage. We adopted frameworks and conventions from old computer games, and adapted them to stage. Hacked gaming controllers (console controllers, joysticks) where the audience controlled the actors live onstage. Our first piece was a game called Playable Demo, where the audience piloted the actor through a short scene in the style of an old LucasArts adventure game, using a torchbeam as a mouse cursor on stage.

A little deeper into our practice, we’ve taken a lot from some of our closer collaborators. Applespiel, obviously, and Coney. Applespiel for their actual genuine expertise in participatory theatre (as opposed to our make-it-up-as-you-go style) and Coney for the superb philosophy and vocabulary around how a playing audience could and should be treated.

Finally, we’ve learned a lot from scientists, particularly those working in the field of participatory co-modelling. This is a form of practice whereby scientists collaboratively construct a working model of a social-ecological system - for example, a region of farmland, or a river system. Then they bring together stakeholders from that system to discuss and debate issues facing it, with the model as a platform to facilitate discussion and compromise. Their tools for audience engagement may be a little rudimentary, but the sophistication of the underlying models they’re using put most theatre-makers to shame.

Young Boho. Jack & David in A Prisoner's Dilemma, circa 2007.

Young Boho. Jack & David in A Prisoner's Dilemma, circa 2007.

What drew you to working in participatory/playful performance forms?

We started Boho in late 2006: Michael Bailey, Jack Lloyd, David Shaw and I. Jack and I had made an interactive scene called Playable Demo in 2005, based on old adventure games. (In the floppy disk era, you would often get a single scene from a larger game as a kind of interactive advert for the whole game.)

We took that format and combined it with the science of Game Theory to make our first show, A Prisoner’s Dilemma. Game Theory is a great tool for game-makers because it breaks real world scenarios into well-defined mathematical structures. We created a whole series of micro-games based on different Game Theory thought experiments (the Prisoner’s Dilemma, Chicken, Dictator, Ultimatum) and threaded a Harold Pinter-esque narrative through them.

That show really placed us in a very particular niche: ‘interactive science-theatre’. What even is that. But it was good to be able to label ourselves as something for a couple of years, even though now we’ve spilled out in a lot of different directions.

Food for the Great Hungers, 2009.

Food for the Great Hungers, 2009.

What's the benefit/advantage of playing with a participating audience?

Ahhh, well, the trick is what we all know now, you and me and all the artists making participatory theatre, which is: the audience is always participating - it’s just a question of how. Sitting passively in the dark watching and not talking is a form of participation - we’re just so trained by theatre conventions that we take it for granted and don’t realise it’s a choice, a compact we all (artists and audiences) agree on.

Same with making site-specific stuff - you realise that the theatre venue isn’t a necessity, it’s an option - you use it sometimes when the moment calls for it, at other times you let it go.

Whatever level of participation the audience engage in, that’s a trade-off. If the audience are moving around outdoors experiencing your work, they’re feeling much more exhileration, excitement, there’s opportunities for happy accidents and beautiful unique experiences, but you run the risk of losing their focus, of them being distracted, feeling lost or confused.

If the audience are seated quietly and watching a well-lit stage, that’s ideal for delivering complex information and making sure everyone sees the same thing, but you’re talking at them rather than having a conversation, and you run the risk of boring them / annoying them if they feel like they can’t leave.

We (Boho) choose the level of interaction based on what we want their experience to be, what we’re talking about, what we want to discuss. If we want to talk with them about how tipping points or regime shifts occur, maybe that’s best if we just explain it as clearly as we can, using whatever theatre imagery works best. But if we want to illustrate the challenges facing local government when they’re evacuating small communities from a potential volcano eruption, maybe we want to give them the experience of trying to make decisions and negotiate compromises with imperfect information.

True Logic of the Future, 2010. Pic by 'pling.

True Logic of the Future, 2010. Pic by 'pling.

What mechanics do you use to encourage and support player agency?

Typically our games are quite short, and there are lots of them throughout a show, interspersed with narrative / storytelling moments, or micro-lectures. That means we can guide the audience through the aesthetic experience quite closely, rather than setting it up at the beginning of the night and just letting them roam free.

That gives us a better chance of managing certain player dynamics - reining in hot players who are dominating the games, or drawing in quieter, more passive players.

But player agency? Not our highest priority, honestly. We’ve usually created quite a curated experience, and though each game is completely interactive, and the whole show has a lot of different states and outcomes (usually in the thousands, if you tally it all up), we’re not running a LARP - we have quite a detailed sense of where we want the audience to go, and we’re happy to take them there.

- David

For a high-speed example of all of these principles in action (more or less), you can check out Jack and Mick's 18-games-in-18-minutes performance at TEDx Canberra:

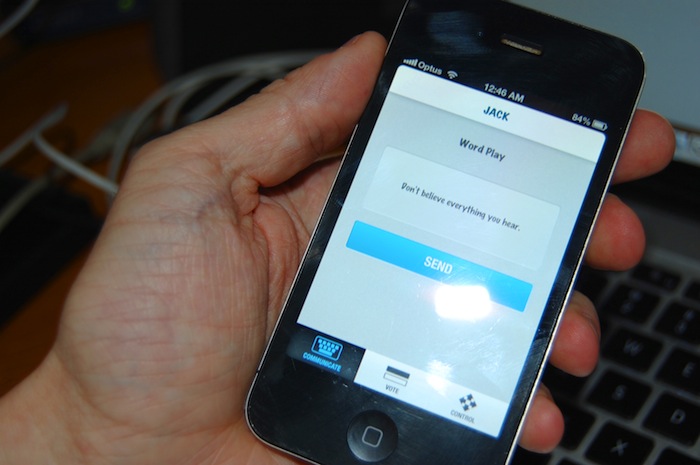

So we're now one week out from opening, and I dropped into the laboratory / performance space to have a look at the bump-in. Jack, Mick and designer Gillian Schwab were working away, and everything is coming together in a sort of terrifying order. Looking around at the extraordinary array of equipment, I thought it'd be a good idea to have a chat about how all this stuff works in practice - what are all the different parts of the Word Play machine and how do they fit together?1. Performers are filmedFirst of all, the audience are in one space (the CSIRO Discovery lecture theatre) and the performers are next door to NASA in the Yarralumla Forestry Labs, performing live on camera. The show uses about eight cameras - action-cams mounted on performers, security cameras that operate over a network, more traditional handicams. As well as that there's an array of prerecorded video and information slides.2. Video is mixed and streamed to the internetAll of these video sources are brought into a controller computer in the Yarralumla labs and director Marisa Martin (with the assistance of an operator) decides which camera is sent through to the live feed and when. There are a selection of visual overlays (maps, diagrams and so forth) which are added to the vision at certain points. Throughout the show, Marisa is live video-mixing (literally calling the shots) based on what's been rehearsed, with some room for improvisation.

So we're now one week out from opening, and I dropped into the laboratory / performance space to have a look at the bump-in. Jack, Mick and designer Gillian Schwab were working away, and everything is coming together in a sort of terrifying order. Looking around at the extraordinary array of equipment, I thought it'd be a good idea to have a chat about how all this stuff works in practice - what are all the different parts of the Word Play machine and how do they fit together?1. Performers are filmedFirst of all, the audience are in one space (the CSIRO Discovery lecture theatre) and the performers are next door to NASA in the Yarralumla Forestry Labs, performing live on camera. The show uses about eight cameras - action-cams mounted on performers, security cameras that operate over a network, more traditional handicams. As well as that there's an array of prerecorded video and information slides.2. Video is mixed and streamed to the internetAll of these video sources are brought into a controller computer in the Yarralumla labs and director Marisa Martin (with the assistance of an operator) decides which camera is sent through to the live feed and when. There are a selection of visual overlays (maps, diagrams and so forth) which are added to the vision at certain points. Throughout the show, Marisa is live video-mixing (literally calling the shots) based on what's been rehearsed, with some room for improvisation. 3. Video footage is received and audio overlaidIn the biobox of the Discovery lecture theatre where the audience, Jack and Mick receiving the feed from the Yarralumla space over the internet. (This is a nice touch as it means that the show can technically be linked in to from anywhere in the world.) At this point, Mick is mixing the sound effects and his original score into the feed. Jack is in charge of synching up the instructions for the audience, which appear on a second projector screen in the theatre, as well as appearing on the audience's phone app. These intructions inform the audience how and when to interact with the performance.4. Audience interact via phonesThe audience send SMSes using their phones OR they use the purpose-built app (which you can download upon arrival at the show) to enter different kinds of input: text questions, votes and sometimes a joystick controller.5. Audience input transmitted to DirectorMarisa receives the audience input on a separate controller computer which collates the votes automatically. She can choose from the different submitted questions and select which to pass on to the actors and when.6. Director communicates with performersMarisa calls through the instructions to the actors, who are each fitted with a radio receiver and earpiece.7. Performers respondThe actors have rehearsed a wide variety of scenarios responding to different audience decisions. Sometimes, though, the audience will give them something totally unexpected and they'll be improvising something new.

3. Video footage is received and audio overlaidIn the biobox of the Discovery lecture theatre where the audience, Jack and Mick receiving the feed from the Yarralumla space over the internet. (This is a nice touch as it means that the show can technically be linked in to from anywhere in the world.) At this point, Mick is mixing the sound effects and his original score into the feed. Jack is in charge of synching up the instructions for the audience, which appear on a second projector screen in the theatre, as well as appearing on the audience's phone app. These intructions inform the audience how and when to interact with the performance.4. Audience interact via phonesThe audience send SMSes using their phones OR they use the purpose-built app (which you can download upon arrival at the show) to enter different kinds of input: text questions, votes and sometimes a joystick controller.5. Audience input transmitted to DirectorMarisa receives the audience input on a separate controller computer which collates the votes automatically. She can choose from the different submitted questions and select which to pass on to the actors and when.6. Director communicates with performersMarisa calls through the instructions to the actors, who are each fitted with a radio receiver and earpiece.7. Performers respondThe actors have rehearsed a wide variety of scenarios responding to different audience decisions. Sometimes, though, the audience will give them something totally unexpected and they'll be improvising something new. For anyone who skipped to the end of all that, the short summary is: There's a lot going on in this show. Now come along and

For anyone who skipped to the end of all that, the short summary is: There's a lot going on in this show. Now come along and  David: Why did you decide to go with smartphone interactivity for this show?Jack: Everyone has a phone. It's an interactive device that's hugely powerful, that everyone knows how to use, and that fit really nicely within the world of the play.Mick: The whole show is operable by SMS, with the intention that the play is accessible to as many people as possible, regardless of the handset they own.Jack: But we have a good relationship with a local iOS developer,

David: Why did you decide to go with smartphone interactivity for this show?Jack: Everyone has a phone. It's an interactive device that's hugely powerful, that everyone knows how to use, and that fit really nicely within the world of the play.Mick: The whole show is operable by SMS, with the intention that the play is accessible to as many people as possible, regardless of the handset they own.Jack: But we have a good relationship with a local iOS developer,  David: What impact does this have on the characters and the show?Jack: We use interactivity to give an audience the opportunity to explore the work from the direction that they're interested in. They can ask us things directly about the world we're presenting, or vote to hear about one thing or another, or even pilot actors around the space. This is hopefully all part of a richer experience for the audience - it adds a liveness and an immediacy to the performance when you know that what the character does next is wholly dependent on your input.David: How do you think this will feel for the audience?Mick: Hopefully it's an intuitive experience for them. It's an unusual format to view a show in, to be sitting in one place and to see it all unfold on the screen, performed in a totally different building, but the interactivity with the audience is crucial - it's really the difference between a live performance and what may as well be prerecorded film. The interactivity makes it theatre again.Jack: I think that when the audience are all huddled together in the darkened theatre, sitting amongst a sea of bottom-lit faces and doing what they can to keep our characters alive, I reckon it's going to feel pretty damn special.Where: CSIRO Discovery Centre, Clunies Ross street, ActonWhen: 7:30pm Wednesday – Saturday 15-18 May, 22-25 May, 29 May-1 JuneTickets: $20 –

David: What impact does this have on the characters and the show?Jack: We use interactivity to give an audience the opportunity to explore the work from the direction that they're interested in. They can ask us things directly about the world we're presenting, or vote to hear about one thing or another, or even pilot actors around the space. This is hopefully all part of a richer experience for the audience - it adds a liveness and an immediacy to the performance when you know that what the character does next is wholly dependent on your input.David: How do you think this will feel for the audience?Mick: Hopefully it's an intuitive experience for them. It's an unusual format to view a show in, to be sitting in one place and to see it all unfold on the screen, performed in a totally different building, but the interactivity with the audience is crucial - it's really the difference between a live performance and what may as well be prerecorded film. The interactivity makes it theatre again.Jack: I think that when the audience are all huddled together in the darkened theatre, sitting amongst a sea of bottom-lit faces and doing what they can to keep our characters alive, I reckon it's going to feel pretty damn special.Where: CSIRO Discovery Centre, Clunies Ross street, ActonWhen: 7:30pm Wednesday – Saturday 15-18 May, 22-25 May, 29 May-1 JuneTickets: $20 –  Boho Interactive has been creating interactive theatre since 2006, but the company's new show brings a whole new element into the picture. Word Play is a 'live cinema' experience, which means that the show is performed live in one location and streamed via high-speed video broadband to the audience, in a totally different location.This is not just an exercise in videoconferencing, however. Rather than a static shot of three performers in a room performing to a fixed camera, the show is more like a movie which is being performed, filmed, edited and screened in realtime. The actors will switch between performing and filming, and the vision will switch between a huge array of cameras as the performance moves through a series of disused CSIRO laboratories.Add to that the fact that the audience will be interacting live with the performers via mobile phone, asking questions, making decisions and in some instances directly controlling the performers in live video-game sequences, and the result is a genuine hybrid of film, theatre and video gaming.A 'live cinema' work demands a very different approach to making a work of theatre, and so Boho is excited to welcome filmmaker

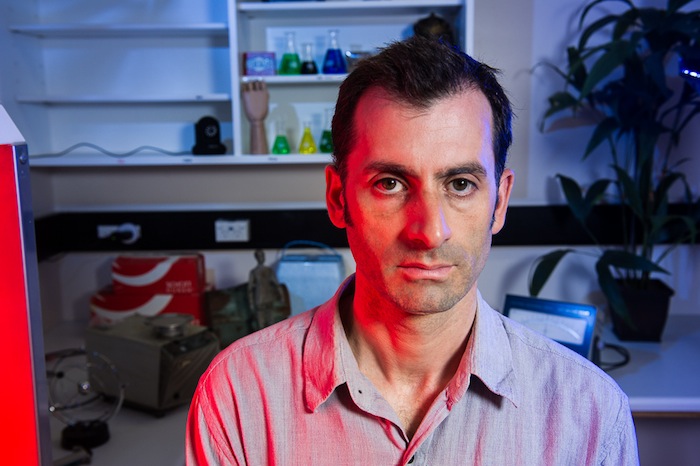

Boho Interactive has been creating interactive theatre since 2006, but the company's new show brings a whole new element into the picture. Word Play is a 'live cinema' experience, which means that the show is performed live in one location and streamed via high-speed video broadband to the audience, in a totally different location.This is not just an exercise in videoconferencing, however. Rather than a static shot of three performers in a room performing to a fixed camera, the show is more like a movie which is being performed, filmed, edited and screened in realtime. The actors will switch between performing and filming, and the vision will switch between a huge array of cameras as the performance moves through a series of disused CSIRO laboratories.Add to that the fact that the audience will be interacting live with the performers via mobile phone, asking questions, making decisions and in some instances directly controlling the performers in live video-game sequences, and the result is a genuine hybrid of film, theatre and video gaming.A 'live cinema' work demands a very different approach to making a work of theatre, and so Boho is excited to welcome filmmaker  I asked Marisa a few questions about her previous work, and about the challenges of creating a live interactive film experience.David: Word Play is the story of a disease that infects language and ideas, and the consequences of a widespread outbreak. I believe you've touched on similar themes in some of your previous work?Marisa: That's right - One If By Will was a short film I made in 2006 set in a post-apocalyptic society where people were afraid to communicate with one another. It asked the question 'What happens when people stop talking?' Within that world it was the story of a couple, and how quickly relationships erode, dissolve and disintegrate when communication breaks down.David: What are the biggest differences in creating a work on screen versus live on a stage?Marisa: One difference is that in theatre there's a much stronger focus on actors, whereas in film I find the focus is much more on the production team. In theatre it comes down to the actors on stage to make it work - they can't just say 'can we do that again?' In film there's a greater focus on the camera and the design. With Word Play, both of those elements are critical and pretty inseparable.One thing that film can do that theatre can't is to invite the audience to focus on particular things, because we can use the camera to direct what the audience sees. In the theatre it's always a wide shot. With Word Play I'm going to mix up the vision - we'll use wide shots, mid-shots, close-ups, point-of-view shots.It also means that we'll be able to play on nuance much more - when the performer's face is as big as the screen, you can do more with less.David: How will the performers respond to the questions, decisions and instructions made by the audience?Marisa: A lot of that will be filtered through me so that's something different to film and TV again because I will be in their ear. I can tell them to tone it down, to move their head because the camera's not in the right spot. It's going to be a different challenge for them. And the second half of the play is going to be nuts - the show becomes a survival horror game.For me it will be like live TV. For them it will be like a mixture of theatre and film-making. For the audience it will be the most unusual experience ever. It will be the unique.Where: CSIRO Discovery Centre, Clunies Ross street, ActonWhen: 7:30pm Wednesday – Saturday 15-18 May, 22-25 May, 29 May-1 JuneTickets: $20 –

I asked Marisa a few questions about her previous work, and about the challenges of creating a live interactive film experience.David: Word Play is the story of a disease that infects language and ideas, and the consequences of a widespread outbreak. I believe you've touched on similar themes in some of your previous work?Marisa: That's right - One If By Will was a short film I made in 2006 set in a post-apocalyptic society where people were afraid to communicate with one another. It asked the question 'What happens when people stop talking?' Within that world it was the story of a couple, and how quickly relationships erode, dissolve and disintegrate when communication breaks down.David: What are the biggest differences in creating a work on screen versus live on a stage?Marisa: One difference is that in theatre there's a much stronger focus on actors, whereas in film I find the focus is much more on the production team. In theatre it comes down to the actors on stage to make it work - they can't just say 'can we do that again?' In film there's a greater focus on the camera and the design. With Word Play, both of those elements are critical and pretty inseparable.One thing that film can do that theatre can't is to invite the audience to focus on particular things, because we can use the camera to direct what the audience sees. In the theatre it's always a wide shot. With Word Play I'm going to mix up the vision - we'll use wide shots, mid-shots, close-ups, point-of-view shots.It also means that we'll be able to play on nuance much more - when the performer's face is as big as the screen, you can do more with less.David: How will the performers respond to the questions, decisions and instructions made by the audience?Marisa: A lot of that will be filtered through me so that's something different to film and TV again because I will be in their ear. I can tell them to tone it down, to move their head because the camera's not in the right spot. It's going to be a different challenge for them. And the second half of the play is going to be nuts - the show becomes a survival horror game.For me it will be like live TV. For them it will be like a mixture of theatre and film-making. For the audience it will be the most unusual experience ever. It will be the unique.Where: CSIRO Discovery Centre, Clunies Ross street, ActonWhen: 7:30pm Wednesday – Saturday 15-18 May, 22-25 May, 29 May-1 JuneTickets: $20 –

Something is wrong.In the last few months, a new disease has emerged that is transmitted not by water, by air, by contact – but by speech. Language. Via text messaging and email, telephone or video.This disease attacks thought itself, undermining our ability to think critically and resist other people's influence. This is an epidemic of harmful ideas and broken logic. And it’s spreading. Whole communities of people, highly contagious, wandering about, unable to talk, unable to take care of themselves, looking for things to believe in.In a few short months, the epidemic has hit a critical mass and gone global. The population of entire countries have been infected and gone under, and all international communications have collapsed entirely. In Australia, the last remaining survivors have been quarantined in bunkers, isolated from any potentially infected communications from the world outside.Now, as food and medical supplies are running short, a group of scientists from a medical research laboratory are about to embark on a last-ditch attempt to release a cure. Boho invites you join us as we open channels to the last functioning research centre in Australia for a lecture that will turn the tide of this epidemic.Don’t believe everything you hear.

Something is wrong.In the last few months, a new disease has emerged that is transmitted not by water, by air, by contact – but by speech. Language. Via text messaging and email, telephone or video.This disease attacks thought itself, undermining our ability to think critically and resist other people's influence. This is an epidemic of harmful ideas and broken logic. And it’s spreading. Whole communities of people, highly contagious, wandering about, unable to talk, unable to take care of themselves, looking for things to believe in.In a few short months, the epidemic has hit a critical mass and gone global. The population of entire countries have been infected and gone under, and all international communications have collapsed entirely. In Australia, the last remaining survivors have been quarantined in bunkers, isolated from any potentially infected communications from the world outside.Now, as food and medical supplies are running short, a group of scientists from a medical research laboratory are about to embark on a last-ditch attempt to release a cure. Boho invites you join us as we open channels to the last functioning research centre in Australia for a lecture that will turn the tide of this epidemic.Don’t believe everything you hear. Boho's new show Word Play is performed on-screen from across the city. The audience are situated in the CSIRO Discovery Centre lecture theatre, while the performers are live-streamed from a laboratory across the city using a high-speed video broadband connection.Using text messages and a purpose-built phone app, the audience are able to interact directly with the performance, communicating with the performers and controlling them through a series of live computer game sequences.Word Play is a performance lecture exploring concepts from epidemiology, a live cinema experience and a hands-on video game in the survival horror genre.Bring your phone.

Boho's new show Word Play is performed on-screen from across the city. The audience are situated in the CSIRO Discovery Centre lecture theatre, while the performers are live-streamed from a laboratory across the city using a high-speed video broadband connection.Using text messages and a purpose-built phone app, the audience are able to interact directly with the performance, communicating with the performers and controlling them through a series of live computer game sequences.Word Play is a performance lecture exploring concepts from epidemiology, a live cinema experience and a hands-on video game in the survival horror genre.Bring your phone. Created in residence at the CSIRO, Boho's new work looks at the behaviour of epidemics, focusing on an ominous trend in medical research over recent decades.As a result of widespread use of antibiotics, almost every type of harmful bacteria has become stronger and less responsive to treatment. Antibiotics that were once reserved as drugs of last resort are now routinely deployed, and the microbes are now overcoming even these final defences.Old scourges such as Tuberculosis are returning, completely immune to remedy. Meanwhile, new and appallingly lethal diseases such as Hendra, SARS and Ebola are increasingly brought into contact with people through evolving networks of human behaviour – urbanisation, agriculture and travel. The results are impossible to predict.Boho's research into this area included a visit to the Australian Animal Health Laboratories near Geelong, Victoria, where we were lucky enough to be taken to Biosecurity Level 3, and visit the room where the samples of Ebola, Hendra, Nipah and SARS were kept.

Created in residence at the CSIRO, Boho's new work looks at the behaviour of epidemics, focusing on an ominous trend in medical research over recent decades.As a result of widespread use of antibiotics, almost every type of harmful bacteria has become stronger and less responsive to treatment. Antibiotics that were once reserved as drugs of last resort are now routinely deployed, and the microbes are now overcoming even these final defences.Old scourges such as Tuberculosis are returning, completely immune to remedy. Meanwhile, new and appallingly lethal diseases such as Hendra, SARS and Ebola are increasingly brought into contact with people through evolving networks of human behaviour – urbanisation, agriculture and travel. The results are impossible to predict.Boho's research into this area included a visit to the Australian Animal Health Laboratories near Geelong, Victoria, where we were lucky enough to be taken to Biosecurity Level 3, and visit the room where the samples of Ebola, Hendra, Nipah and SARS were kept.  Where: CSIRO Discovery Centre, Clunies Ross street, ActonWhen: 7:30pm Wednesday - Saturday 15-18 May, 22-25 May, 29 May-1 JuneTickets: $20 -

Where: CSIRO Discovery Centre, Clunies Ross street, ActonWhen: 7:30pm Wednesday - Saturday 15-18 May, 22-25 May, 29 May-1 JuneTickets: $20 -